I blame, my parents!

I blame them for being fascinated by nature and watching on television the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau TV film series in the reruns in the early and middle 1970s, and allowing me to watch it so that I became entranced with nature and then stated pretty early on that I was going to be (i) a vet; (ii) Jacques Cousteau’s indispensable trainee and failing that (iii) a zoologist – at 6 years old I thought that meant that I would get to look after the animals in a zoo. Options (i) and (ii) fell out for various reasons but I stuck to my guns on option number (iii) even though it meant I would be a scientist and not an animal care taker.

I simply could not wait for my biology lessons to start at secondary school (14 years old), my first teacher was a very laid back kind of botanist who was finishing his own PhD thesis and took the year long teaching stint I guess to earn money whilst still having time to finish the thesis write up. I loved my first year in studying biology. A sort of academic school nirvana. Subsequent to that first year though I was disappointed because this teacher left our school to go onto other things. He had been as passionate about biology as I thought one ought to be and I thought it would be hard to have another replicate that – and I was right. I always quipped later on (thinking I was so funny) ‘How could the study of life be so dead in the classroom?’ This was nothing like the sense of wonder and joy that I had originally looking at those wonderful Jacques Cousteau films.

As my mother will attest if you asked her though, once I get a bee in my bonnet then I really can put the stubbornness of mules to shame and I persevered through to getting a BSc with honours in Zoology.

I give a brief autobiography because I feel I have an understanding of how biology is taught, or at least how it was taught right through to tertiary level.

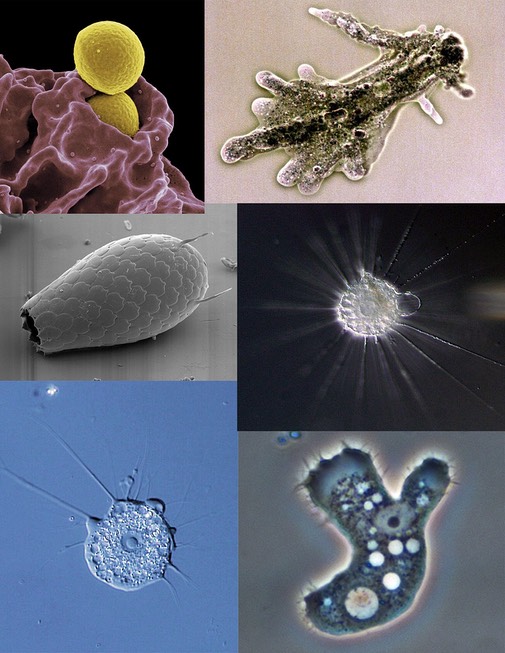

Normally the thinking is that when you teach something, you start with simple things and then gradually build up these simple things to more complex things. That makes a lot of sense and avoid what educational psychologists call ‘cognitive overload’, a fancy way of saying that it is best if do not give pupils too much to think about at the same time. However, in biology that equates to starting with what is considered ‘simple’ organisms and then building up to more complex organisms. What could be more simple than a single celled organism – say an amoeba? And then the biology teacher could gradually work up to the apex of complex biological organisms – why that would have to be humans would it not? That is certainly how I was taught. I am not saying it was the absolute worst way in the world to teach biology, but I am saying that with the benefit of hindsight, there’s a different way of thinking about how to teach biology that will make far more sense than this route.

First of all let us abandon any notion of what objectively constitutes ‘simple’ versus ‘complex’ – as in an amoeba is a simple organism and a human is a complex one. We should abandon this, because often ‘simpler’ can mean ‘more efficient’ or ‘more generalist’ or ‘better able to survive’. Sharks, as apex predators, are considered to be some of the ‘simpler’ chordates (animals with backbones) because they evolved before bony fish, since their ‘bones’ are really cartilage. However, they have remained on this Earth virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. If biological ‘success’ is measured in longevity of a species, then sharks have to be one of the most successful of the ‘chordate’ animals.

Another approach we could try but I am suggesting we drop; and that is to start with cells and then work our way up to tissues, anatomy, individual organisms, groups or organisms, species and then ecosystems. The argument goes that since cells are the building blocks of life, then we are studying the foundation of all of biology. Sadly this does not equate, it is the wrong level of description to learn about populations of species living in an ecosystem. As an analogy, it is like learning about quantum physics and the associated non-sensical (to us) equations to describe how petrol burns so that we can understand how to take directions that allows us to travel from say the capital of Fiji, Suva, to the capital of Japan, Tokyo, on a commercial jet aeroplane.

Other ways to teach biology

In a nutshell, teach biology initially through the human body

We have a programme that now includes movement and exercise for health reasons (trying to form healthy habits to stave off the onset of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in middle and mature ages) rather than sport. We also have a nutrition programme where we want to educate children to know far more about their food, including an idea of what the major food categories are, and how to read the food labels of food items and know how that is either good, or bad for you. Finally we have students learning how to do first aid and also the rudiments of learning how to do life saving in swimming situations.

However, we have found that children do not really know what their body is made up of, and so all the health benefits of doing exercise; the benefits of eating certain types of food and avoiding others, and the logic behind why one does first aid or lifesaving procedures in a certain way is a mystery.

Starting with the human body’s biology, is a way of giving information that a child can use in their exercise, diet and life saving/1st aid course work.

To be fair most modern biology programmes do actually have a strong human biology component in them – but they are often short, occur in senior years and have no direct links to healthy lifestyles and good nutrition information or why first aid and life saving is done the way that it is.

Last year we started with our Year 4s (10 year olds) with the skin, the skeleton and the circulatory system (without the lungs). We introduce them to gross structure (aka anatomy); tissues and very roughly how they work (aka physiology) and some of the cells (aka cytology). Simple things that they can touch, feel or relate to. It’s a five year programme. In Year 8 they learn about the hormone and reproductive system – just in time for puberty!

During this time they will have learned about why drugs (especially recreational ones) affect our mental state; muscles and other connective tissues can become torn and how this can be prevented (hint it’s called a warm up and warm down); why your kidneys will thank you if you drink lots of water on a daily basis. They will learn why we do aerobic exercise (heads up it is not to take part on the New York marathon); why resistance training is essential even when we are in our 70’s and 80’s and beyond; and how tai chi, or dancing, or yoga will help prevent hip replacements for individuals in their 60s; why CPR is not the first thing that you give a person who is not breathing and has just been fished out of a swimming pool if there are strong reasons to believe that they have their lungs full of water.

They get to learn about staying healthy (– hey it’s bacteria and viruses that we’re learning about now), and rudimentary understanding of the health regimens that we are put on as patients (– and now they learn about evolution because of a concern about drug resistance in micro-organisms).

I think if I had been taught this way, then my sense of original wonder at the Jacques Cousteau television specials, would have been far closer to the actual study of biology that I imagined.

Biology then is a way of empowering our young pupils to be more aware of their bodies. Everyone needs knowledge of their bodies. In the process they happen to learn about biological concepts such as cells, tissues and adaptations in our anatomy that are used later on in formal biology lessons in Year 9 and above. Knowing about human biology allows us to study down to the intra-cellular structures and processes such as mitochondria, or DNA replication and genetics. Human biology is a springboard to learning about comparative biology (eg starting off with other primate species and then we get down to plants, fungi and the rest of the living world) as well the diversity of life (classification) and systems theories in biology (ecology & evolution).

Who knows, a teacher at advanced classes might even talk to their students who have medical aspirations, about the amoeba!